Third Culture Kids

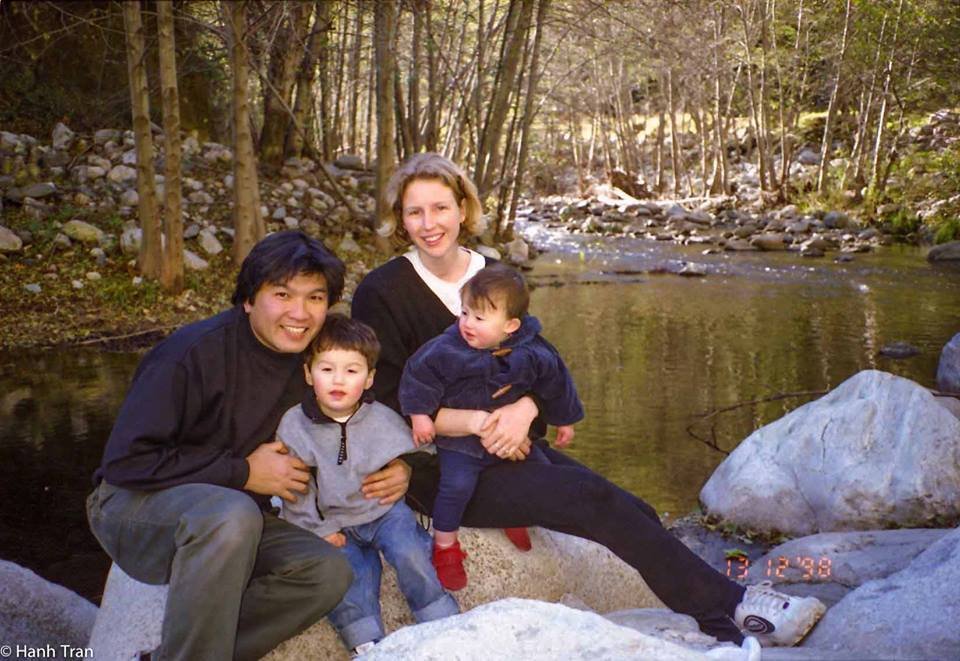

James Purnell Tran is a Naarm based media worker, best known for his documentary and photography work. This photo series captures his conception of Third Culture Kids.

It’s a universal cliche that hard working people immigrate to give their kids a chance at a better life. The physical reality of immigration is reliably traumatic, especially during our parents’ generation, but that’s no effective deterrent for the parent who believes. In ones and twos and threes they set out on planes and boats and Nikes. Learning the essentials of English from phrasebooks and the slurs from alleyways or senior management. Sending a week’s food home in small change, paving the way for a relative to come and sleep in the same room.

The pain of relocation can manifest with such weight that the task of expressing how difficult one’s journey has been becomes just another hardship that’s best avoided. To many an immigrant child, the scars and pathologies of our parents are as unknowable as the rooms they were raised in or the way water tasted in the old country.

And now we lucky third culture kids persist in the first world. Equally acknowledging and participating in excess with every business hour and staring down the barrel of a century of climate consequence. Accepting the idiosyncrasies of our parents, unable to express our anxiety about the future lest it be compared to the pain of their past. We toy with the knowledge of our parents' sacrifice and pray for as clear a direction to point our own children.

Things are bad, but where could we move that’s better? And every day we stay here, the ocean becomes a little bit longer.

James Purnell Tran is a Narrm based media worker, best known for his documentary and photography work. He is the brother of Mai Hà Tran who previously contributed this piece to the writing corner. More of James' work can be found at @everything_jame and his website everythingjame.es

On Becoming My Father’s Father

Dedicated to Ray, my dad

By Clinton Chan

7 minute read

Dedicated to Ray, my dad

To this day, I distinctly remember an experience from the age of 15 that said a lot about the relationship my dad and I had when I was growing up. It was a Sunday and my dad, being the committed dad he is, was driving me to my weekly tutoring classes in a faraway suburb (how very Asian yes). The ride took about 50 mins. I remember hearing an advertisement on the radio talking about HIV testing. Knowing how uncomfortable it would make my dad, I deliberately piped up and asked him what the best way to prevent HIV transmission was, baiting him into an awkward encounter.

I am not joking when I say that it took my dad the rest of the car ride, sitting in awkward silence for 40 mins, before he found the words just as he was dropping me off in the carpark, to say in a forced but clear voice: “Yuu do not have seks with a girl dat has AIDS”. He promptly sped off and we never spoke about HIV or anything sex-related again.

Whilst you and I might laugh at this experience now that we’re adults, this interaction was the epitome of our relationship. I wouldn’t say that I had a poor relationship with my dad, but nor would I say we got on like a house on fire.

On paper, he has been a great dad: he held a stable and high-paying job, he was committed, non-violent, and dependable in key ways. But like a lot of men since Generation X (and arguably the Boomers), my relationship with him lacked emotion and depth — I could barely ask him to articulate how he really felt about my sister and I, let alone ask him for guidance on my deepest insecurities. When it came to emotional intelligence, self-actualisation, or even a simple friendship, I often felt my dad had as much presence as a cardboard stand-in for a real dad.

My dad grew up in 1970s-80s Sydney, a far cry from Sydney today

However, as I’ve gotten older I’ve learnt to accept, with a great deal of dissatisfaction, that my dad will never be the ideal male role model I want him to be. Interestingly enough, as I’ve gotten older I’ve felt myself become that person for him — I am becoming my father’s father.

I want to talk about my experiences on this journey so far in the hope that other men growing into adulthood will cast aside the unmet needs of the past, and consider turning the tables by assuming the male role model they (and their fathers) have always wanted.

“Be Better”!

From the age of 13 I became acutely aware that I lacked a role model in my dad, especially when it came to emotional support.

Knowing this, I confronted him several times through my teens about why he wasn’t filling that role. I don’t think I went about it the right way because I ended up calling him a “bad dad”. This was a mistake and I regret how I phrased it, but like a lot of boys and men I knew at the time, as I do now, that I was missing a key part of my development.

Coming back to the HIV story, it was moments like this interaction in the car that both bemused and disappointed me by demonstrating the immense gap between what I wanted in a male role model, and the reality of my situation. Instead of a resolute and self-aware father figure, I got the socially anxious math nerd.

This gap festered away in my adolescent brain, like a wound on the brain that refuses to heal as the rest of the body transforms and pulses with hormones. “Be better!” I would tell him in my head, but with time I let go and grew to quietly resent my dad’s lack of guiding presence in my life.

Outgrown

As I gained my own experiences and grew more independent, I felt that I had “outgrown” my own dad, that I was by all accounts the “better man”. My quiet resentment and disappointment persisted deep down but had crucially evolved into pride and condescension.

I just chose not to say much to him because he seemed to not have much that was meaningful to say to me. Instead, I looked to “other” role models at school/university, at work, and amongst my own friends — I became a heat-seeking missile looking for validation.

I didn’t hate my dad, I just thought he was the biggest goof

I didn’t necessarily voice my avoidance of my father but from how little time I spent at home, and how little my dad and I had to say to each other, especially during my university years, it was clear to all that there was something thicker than blood.

Through my interactions with men outside of the home, I learnt more than I had ever hoped to learn from my own dad. I spent time with university lecturers who taught me about 2nd and 3rd wave feminism and why it was not a threat to “manhood”, and how to appreciate and critically evaluate these viewpoints without resorting to misogyny (or misandry). I worked with male bosses who worked from home most of the week and took time off because their partners had to be in the office. These men were not threatened by female authority either. I am grateful that these men stood in for my dad when he was still trying to figure out what kind of man he wanted to be for himself.

Becoming

Everything changed with the passing of my grandmother last year (my dad’s mother). I worried for him because I knew how attached he was to my grandmother, and I called him more frequently to see how he was going.

Crucially, it dawned on me through the grieving that even though my father was getting older, time only served to peel back the emotional barriers he had put up. With the loss of his last parental figure, I realised that at his core he was not that different to the 12-year-old boy who had arrived in Sydney in the 1970s.

I know my dad didn’t have a good relationship with his dad, the two barely spoke. He also dealt with seismic racial prejudices that I am lucky to only see a glimpse of in the 21st Century.

So I started a journey to begin questioning what it meant to be a man, joining a casual group of other men in monthly conversations and reading up on modern masculinity particularly Steve Bidduplh’s book “The New Manhood” which has been formative.

One of the takeaways that I gained form this book was that “Your dad is not who you think he is”. Knowing that life is short and that people do change, I took the chance and called up my dad to go for a hike the first of several father-son outings.

When we got talking I was honestly surprised at how coherently he spoke. For the longest time, I assumed my dad was an emotionless automaton living in the dictatorship of my mother. But instead, I found myself reconnecting with an experienced but unsure voice, not a tortured one, a voice that was beginning to meander and articulate the joy and inevitable suffering that life had to offer.

Spending time with my dad has meant that we can rediscover what it means to have fun together again

For many years I sat there expecting to receive love and to be guided by my dad into the battles of life. However, I am very lucky that I have grown far more emotionally intelligent than he might ever know. It is now up to me to help him gain an emotional and introspective voice he had never learnt through his own dad or other male role models, to ask questions, and to frame his experiences with words and affirmations that might sound alien to him, but feel homely.

To other young men, I urge you to consider this and do the same when you are ready. Yes, you will have years of resentment, anger, pride, and a fiery urge for something better. But one day all of this may be behind you and you will discover that your dad needs you to become your father’s father.

Through all this time, my dad was hoping that I would in fact turn around and have the courage to say “I love you” and that I would check in on his mental health. He wanted me to be his mirror so he could learn to imitate my words and actions, breathing new life into them as his own.

Cultural Purgatory

Why I Don’t Get Along with Other Asian Australians

By Clinton Chan

8 minute read

I’m going to be blunt because I don’t know how else to speak about this - I don’t really get along that well with other Asian Australians.

This probably sounds ludicrous as somebody who writes largely about the experiences of Asian Australians. It also reeks of internalised racism - I get it.

What I mean is that for much of my life living in Australia I have felt weirdly disconnected from international students and other 2nd or 3rd-generation Asian Australians. Naturally, I also don’t feel entirely at home amongst white Australians either.

I was having dinner with my parents several weeks back and I revealed the same sentiment to them, only for them to stare at me confused and ask “so what do you think you are then?”. I shrugged and just said bluntly, “Well I’m just me”.

It does sometimes sound lonely to be honest, to be stuck in this culture purgatory where there isn’t a particular identity or set of status values you can ascribe to. You can’t beat your chest in an almost nationalistic way and say “I am X identity because I do XYZ” or “I belong to this tribe”.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been out on my own. I wanted to share my experiences in the hope that maybe there are other people like me.

Growing up it often felt like my life was an oddity, like the Truman Show, but I was the only one watching it. Source: Unsplash

How this came to be - I struggle to stay friends with other Asians

I realised this for the first time in my life when I entered university and actually met lots of other Asian Australians - almost too many others. I went to the University of New South Wales (a very “Asian” university) and although I didn’t study Commerce/Business (surprise surprise!) I volunteered with lots of organisations which led me to befriend lots of Asian Australians.

For the first year or so it was almost a honeymoon period. For some of us we just clicked. Growing up I’d never really known any other Asian Australians. I grew up in a Cantonese neighbourhood but went to a fairly white/European primary school before going to a fancy private school that had less than 10% Asian representation, a good chunk of whom were international students who kept to themselves. I was used to being the minority and I was also used to code-switching to avoid sticking out for my perceived “Asianness”.

So when I found a community of other Asian Australians, it was a dream for a time. I didn’t have to explain why the lunch I brought to uni smelt funky, or why on certain days of the year I couldn’t hang out with my friends after 5pm. We also bonded over similar familial experiences and the pressures of parents wanting us to be high-achieving.

It is cringey, but hey it was fun while it lasted. For a time it was the highlight of university. Photo provided by author.

However, it wasn’t long before I felt something was amiss. Outside of growing up in somewhat similar circumstances, we didn’t actually have the same interests. As I grew older and developed my own personality and explored multi-faceted interests, I often diverged with them.

Though it may sound reductive, I was never really into things like karaoke, K-pop, or bubble tea, or hardstyle raves like many others were. But outside of these superficial interests I also felt that I approached life differently - I didn’t have much of a sense of filial piety at all and I had a different risk tolerance to most other Asian Australians, and was gawked at when I mentioned that I had white friends who I was close to.

Centralising identities

Of course all humans have different interests, and it would be extremely harmful to paint all Asian Australians the same way. But, what I was seeing was a performative centralisation and reaffirmation of what it meant to be Asian Australian. It’s not uncommon for migrant diaspora communities to not just intermingle, but to seek out a unique and discernible identity that might be different to the majority population around them.

For my Asian Australian uni friends this meant creating a near-homogenous group identity, and most importantly having close friends who were mostly Asian with similar cultural values. This performative group identity is obviously not absolute, but there is certainly a “locus” of behaviours or values that are explicitly or implicitly collated for the purposes of constructing this identity. The community itself then embodies and reinforces this central identity through self-actualisation and performing this identity by aligning their behaviours and sense of self with the group identity. For you social psychology nerds, this is called self-stereotyping and accentuation in “self-categorization theory”. Ultimately what that meant was that, if I was in the “ingroup” with other Asian Australians I was expected to hold most of the same interests and nigh-Confucian values - otherwise, I’d implicitly or explicitly be rendered in the outgroup.

It sure isn’t the only Asian Australian identity, but the one I speak about is so prominent even the New York Times wrote a piece on it.

Young Asian-Australians at the Sanctuary Hotel, a gathering place in Sydney for members of the “little boy” and “little girl” scene. Credit: David Maurice Smith for The New York Times

As with all group identities, where this is a locus, there is also an outer realm, an opposite identity. As I got older and quickly lost interest in going to Korean BBQ or hearing about careers in the “Big 4”, I realised that I was on the outside and was slowly set adrift. This coincided with the time that I came back from studying/working in China for almost 1.5 years, where I discovered that I also wasn’t very Chinese.

So there I was, an outsider to both my heritage and the diaspora community.

What if there is no “Asian Australian”?

These days, I try to have a diverse mix of friends. There are still plenty of Asian Australians I see on the reg, but I also try to keep fairly diverse company - after all Australia is diverse so why shouldn’t my friends reflect that?

I do still try and make an effort to interact with other Asian Australians and recently joined an Asian Australian community built around discussions of our unique experiences with mental health. Interestingly, during these interactions I certainly do connect with some members but not all, and often quickly find myself alienated again as I only share a small handful of the experiences or values of others. I don’t think I’m “above” anybody else at all, and I’m certainly trying to make a strong effort to stay connected to this community.

But what if my notion of “Asian Australian” is just a single subculture amongst the vastness of Asian Australians across all generations? What does it mean to be Asian after all? My guess is that I may have taken a fairly reductive view of the Asian Australian identity or worse still - conflated a misalignment of cultural values with a difference in socio-economic status, and my privileges as a straight Asian man. After all, my risk-taking behaviour and preferences for exploring other cultures and communities likely comes from the comfort and abundance in my upbringing.

All that I can say is, it’s likely all of the above. I have little doubt that most people’s identities are an intersectional smorgasbord much like my own. So it’s less a cultural purgatory and more a multiverse (how 2022) of different Asian diasporic sub identities, with each person taking up their own universe.

I am after all just my wear wacky self, and that’s ok too.

Building Transgenerational Joy in a Time of Grief

By Clinton Chan

8 minute read

In late July this year, my extended family experienced something we had dreaded for a long time. My grandma, the matriarch of our family, passed away at the age of 90.

My grandma had been the anchor of our family for decades - she’d not only helped bring up 7 children of her own after migrating our family to Australia from Hong Kong, but she also nurtured 17 grandchildren to adulthood.

However, in the weeks since her passing, and as I spent more time thinking about my grandma’s life, I have felt a tonne of pressure to live a life and leave a legacy as consequential as hers. I have felt burdened with the feeling that the only way to honour my grandma’s legacy is by setting and exceeding hopes and dreams as lofty as hers.

I suspect that other people of colour who are living lives significantly more privileged than their ancestors might feel this way too, and I wanted to dive into this and the idea of “transgenerational joy”.

The life of a real “Iron Lady”

Grandma was born in Dongguan, Southern China in 1932 to a farming family. She had a gruelling upbringing - from a young age she helped my great grandparents with rice farming and took produce to the markets several times a week, often travelling by foot for hours. She didn’t have an extensive education and left school at age 7 to help with the farm.

Grandma toiled rolling rice paddy terraces like these in rural Dongguan

Not long after she was born, the Japanese also invaded China, marking the start of WWII. Her childhood was overshadowed by the scarcity created by the War, and because her family was quite poor they relied on eating only taro and sweet potatoes to get by.

When the Communists declared victory over China after the Chinese Civil War in 1949, she was soon to be married and had already given birth to my eldest aunt. She didn’t have a whole lot of say in the marriage either. At that time, grandpa was a cook in Hong Kong, then still a British territory. Grandma decided to make the demanding journey from Dongguan to Hong Kong to reunite with grandpa and start a new life in the “Western” world. The journey took several days by foot and was a challenging trek for a young mother with a toddler and her elderly parents. They settled in Hong Kong, and in the years to follow my other aunts and my dad were born. In total, they had 7 children with some miscarriages in between.

Hawkers were illegal in 1950s Hong Kong

To supplement my grandpa’s modest income as a cook, grandma sold fruit, vegetables, and sometimes fish on the street as a mobile hawker. For years she hustled, carrying her wares on her shoulders with a bamboo stick around the New Territories, often having to evade police as hawking was illegal.

Years later, my grandparents made another life-changing decision to relocate the family to Australia where my grandpa would work at a new Cantonese restaurant in Sydney. Hong Kong turned out to be more crowded and lawless than they’d hoped and they dreamed of an easier life in Australia. However, on arrival in Sydney their life was anything but “easy”. The 1970s and 80s were a rough time for a simple Cantonese woman, who didn’t speak any English or have a solid education. She had to create a new life for herself and her 7 children with nothing but her wits and grit.

But, in the decades since arriving in Australia, she not only put all of her children through school, she lived long enough to see them all get married, establish comfortable lives, and raise grandchildren who didn’t have to farm or hawk vegetables for a living.

The whole family in Sydney in the early 1990s

Ancestral pressure

Why am I sharing all of this? This story is not very different to the experiences of most migrants arriving in the Western world.

I am sharing this because I hope I am not alone when I say that I place a lot of pressure on myself to grasp and maximise every opportunity that life has given me, knowing that these opportunities weren’t available to my grandma.

I know that my grandma lived a life of extreme hardship and migrated constantly through her life so that my aunts, my dad, and her unborn grandchildren could access these opportunities. Even in old age, grandma lived the same simple and no-frills lifestyle from her childhood so that she could spend her pension and modest savings on her children and grandchildren.

If you are a child or grandchild of migrants who moved to the West to live a better life, this knowledge of ancestral sacrifice can be all-consuming and lead to negative internalised thoughts.

Throughout my life, when I have come up short in meeting the goal or ambitions I’ve set myself I’ve cursed my own laziness or lack of focus. I often thought “What would your grandma think? She lived through something a thousand times worse and you can barely do X”. During her life grandma never guilted me into doing anything by reminding me of her sacrifices - but since her passing, I have started to guilt myself into doing more with my life.

Understanding transgenerational joy

Recently, I spoke to a mental health counsellor at work who specialises in navigating mental health for BIPOC folks. I asked him about how to resolve the guilt and pressure that I have put on myself throughout my life and of late to “honour” my ancestors.

His answer was this: the best way that we can honour the legacy of our ancestors is not to carry that transgenerational trauma with us as guilt, but to live with transgenerational joy in our present life.

This means not being so hard on ourselves when things don’t go to plan, and not setting overly demanding goals for ourselves to somehow “make up” for the ancestral sacrifice. Sure our ancestors had to persevere through harsh circumstances, but they did so so that we could have the freedom to live our present life with all its richness and flaws.

It doesn’t make sense to honour their hardship by living a life of hardship too. If we did that we’d probably end up directly or indirectly guilting our own kids into setting unreasonable expectations of themselves because we made similar “sacrifices” for them. This pressure would continue being passed down for all future generations, each feeling indebted to those before. Surely, this is not what our ancestors wanted when they dreamed we’d have a “better life”.

To conclude, I extend this closing thought not just to myself and my family, but to all those experiencing grief or being reminded familial sacrifice and transgenerational trauma - transgenerational joy is just as important, and we owe it to ourselves to manifest it.

Half This, Half That

By Maya / Mai Hà Tran

10 minute read

I sat across the table from him, letting the crunching sounds echo throughout the room. In one clenched fist, a knife, and in the other, a crisp cucumber. He starts his routine of cutting the slices into shapes that allow for maximum sauce capturing. The carving is meticulous and nonsensical. His hand guides the blade in smooth motions away from his body.

The knife goes down and the chopsticks are armed. Now for the reward. The cucumber slice is submerged into a whirl of fish sauce and floating chilli islands. It swells. The perfect bite awaits. Crunch. And then more crunching. And the expedition starts again.

Who are you?

You are strange.

What are you doing?

It confuses me.

Are we really the same?

I don’t recognise you.

The importance of my cultural identity never really sunk in until after my dad died. Up until that point, it was used as an explanation more than anything else.

“This is why my lunch looks weird”

“This is why our kitchen has an odd smell”

“This is why my dad is different.”

It was a cheap escape from further questions. An axe to misguided curiosity. But rarely would it actually end there.

“What’s your Chinese name?”

“I’m not Chinese”

“But you’re Asian right?”

“Yeah, but only half!”

I would say that last line almost in defence. Desperate not to be categorised by what appeared to be an outlier in my DNA. I wasn’t going to claim to be something I wasn’t.

I continued like this into high school. Dodging questions about my ethnic ambiguity and avoiding my dad like the plague. He drove the school bus. At lunch, I would sometimes see him walking along the garden beds with his arms behind his back, his eyes peaking over his rectangular glasses. He would bend down, pick something from the foliage and pop it in his mouth, crunch and continue. I would catch my classmates staring too. A quick diversion would surely stifle my embarrassment. “Hey! Everyone’s playing frisbee on the top hill. Let’s go!”

But then we went to visit dad’s family. A 20-hour flight landed us in a humid and bustling Los Angeles, a rude shock to our cold Melbourne bodies.

Dad is one of ten children. That’s a lot, even by South-Eastern standards. There certainly weren’t a shortage of uncles and aunties. You can only imagine what our welcome party looked like at the airport when we finally rocked up.

“Oh, you look just like your mother, beautiful girl!”

Huh? My mum? But she has pale skin, blue eyes and wild blonde hair. I am simply not that. But I do have her freckles, thrown in no particular order around my cheeks. More things for people to find puzzling about my face. My aunties’ faces were smooth and clear with not a blemish to distract. I wanted to touch them and feel the softness they possessed. If I flicked off my pesky freckle stains, maybe I could look like that too.

We sat around a table of animated voices, rejoicing in fits of laughter and wide toothy smiles. I tapped my cousin on the shoulder. “What are they saying?”

“They’ve missed you. Last time they saw you, you were drooling in their arms. Now you have to lean down just to hug them”. Another laugh broke out. I laughed too. It was certainly a surreal thought.

This is when I started to realise that I was stuck in a sort of limbo. In a room full of family, where do I sit? With my brothers, as clueless as me? With my cousins, forced to translate every word? Little did I know, this conundrum would be a reoccurring one for the rest of my life.

Where do I sit?

That question has become a lot harder since losing dad. A truly important link was lost that day. The gateway to my heritage had become that much more unattainable. No one was tying me to this world of “different” anymore. I didn’t have to figure out who that person sitting across from me was anymore. Well, that’s what I wanted, wasn’t it?

The kitchen became less vibrant. The smell went away. Leftovers emptied from their Tupperware containers. The wok no longer stood as a proud ornament on the stovetop. Condensed milk was no longer poured into the coffees, and there certainly weren’t cucumbers at breakfast anymore.

But this is what I wanted, wasn’t it?

How wrong I could have been. What I would do to guide my younger self now. To show her just how rich my childhood was because of “that half”. She would grow up to treasure that part of her identity more than anything else. Jump at any chance just to be “that half”. Feel how it felt as a kid to be surrounded by those beautiful round faces at the table that day. Oh, how she will long to be “that half.”

Where do I sit?

Want to know a secret? I get to choose. How good’s that?! That’s the part they don’t tell you. You can wear the most beautiful Áo dai’s without anyone labelling it as a cultural appropriation. You can switch between two different names to confuse people. You can cash in on some brownie points at the Asian grocers, simply by being a halfie. They can’t get enough of us!

However, with the weight of decision-making comes some guilt. The guilt of copping out on the less desirable aspects of both your cultures. The internal politics begin. Should I berate white society for all its flaws or milk my white privilege for all its worth? Should I bind myself to traditional familial expectations or carve out a non-conforming path by detaching myself from those very values? How can I be an ally to the Asian community as well as being an active member of it? The questions are relentless and insurmountable. Unfortunately, my parents never handed me a guidebook.

Being biracial is like being on a seesaw. It’s fun for a bit but then it becomes disorienting. A weak analogy perhaps but it has always been a visceral image in my head. I picture myself as a child navigating those ups and downs. I wonder whether my future children will have seesaws of their own. I worry about the further disconnect they will have from their Asian roots. Will their cultural identity become even more diluted than mine? I don’t want to be responsible for that. I don’t want them to resent me like I did my dad all those years ago.

So, where do I sit?

Well, the truth is, I don’t really know. But I wouldn’t want it any other way. I get to experience two cultures and it’s flippin’ phenomenal. I forget the rest of you don’t get this. How do you live? I get to live a life that extends far beyond one border. A bridge between two cultures. A voyeur of both sides. My European and Asian ancestors are brought together because of me. They are forced to accept and make peace with one another in spirit. An unusual assimilation perhaps but a beautiful one all the same.

Put simply, my identity is a cornucopia. That’s how my dad would describe his food at dinner time. An abundant array of good things, mixed together like a bowl of swirling Phở.

So let me introduce myself.

My name is Maya / Mai Hà and I am Vietnamese-Australian. I sit right here.

Love and McDonalds

By Vincent Leung

10 minute read

An English muffin, a sausage patty, and a disc-shaped egg.

That’s all there is to a Sausage and Egg McMuffin.

If you’re feeling fancy, you can add a hash brown, fried until it’s golden, to round out the symphony of a salty, slightly sweet, crunchy, chewy, fatty, tender and gob-smackingly delicious breakfast. And it was exactly what I looked forward to every week.

Food’s an important part of a migrant family. My parents were no exception. Without fail, after picking my sister and me up from Chinese school on Saturday morning, we’d go straight to yum cha for lunch with our grandparents in tow. Hot bamboo steamers would emerge from steam-filled kitchens and a cacophony of sounds would swirl around us, in Cantonese and Mandarin, as we dove into dumplings, baked goods, cheung fun and phoenix claws (also known as chicken feet).

Delicious.

If it wasn’t yumcha, we’d go to our local cha chaan teng (HK-style cafe) for a quick A or B set menu meal - $9.50 for a massive plate of noodles or rice, plus a drink. Two plates could feed the four of us, and my mum was immensely proud that we were saving money.

“See how cheap this is? They sell these for $11 at other places” she’d lecture us as we dug into the salt and pepper chicken ribs on rice, or pork chop with black bean sauce on spaghetti. “And you get a drink for free!” After lunch, they’d drop us off next to the butcher, and then split up to go hunting for bargains, finding the marginal increments of $1/kg saved here and there, crowing triumphantly over their purchases when they met up again.

If my sister or I curiously poked our heads into a cafe to look at their selection of brownies, or sandwiches, or focaccias, my parents would yank us away.

“Those are expensive. We already have those at home. We can make it for $5, why would I pay $10 for theirs?”

And so, McDonalds. Sunday morning, if we could get up early, our parents would consent to letting us go to the Happiest Place on Earth. To them, it meant 2-3 hours where they didn’t have to supervise us too closely and the holy grail of a cheap and tasty breakfast for fussy kids. To us, it was a secret infiltration of the white person, Australian breakfast - a subversion of the typical Chinese fare we would get at home. Dad would drive us all to Maccas and set up with a newspaper, and Mum would send us to find another newspaper for her from the surrounding tables. After finishing this quick task (who could say no to a cute Asian kid?), we’d eagerly run up to the counter to order our Sausage and Egg McMuffin, Bacon and Egg McMuffin (for my sister), and beg Mum to get us a hash brown or two along with them.

“*Sigh* so unhealthy!” A pause. “If you can tell me how much it will be all together, then maybe I’ll buy it for you”. And she usually did! Other days, maths was hard.

(Every opportunity is a learning opportunity - parents, pay attention.)

As we opened these warm, muffin-size packages, the sacred oath of a delicious breakfast wafted through the air. The crackle of the paper unwrapping created a Pavlovian reaction that is universal - our saliva glands working in overdrive to get ready for the meat and egg flavour bomb about to occur.

It’s all in the muffin, you know? The patty and the disc-shaped egg are the key foundations of flavour, but the muffin provides the crunch, the chew, and then hits you with an eldritch, supernatural seasoning on the outside that ties everything together in a way that reminds you of the warmest, softest bed you’ve ever slept in after a day in the cold, wet world. You had to savour every single bite. Often, I would unthinkingly take a gigantic bite in excitement, and then morosely take squirrel bites of the rest of the muffin to make sure I was eking out every morsel of satisfaction for my mouth. My sister was much more patient, slowly chewing through her muffin thoughtfully, making sure she was neatly eating through the disc of deliciousness.

Breakfasts have always been a point of contention in our family. I was never really hungry in the morning, but Mum would insist on us eating breakfast. We ate all manner of things, begrudgingly - porridge, cereal, toast - anything that was appealing and (sort of) healthy. She would be on our back every morning to have a hearty breakfast (usually eaten in the car on the way to school) and a big cup of milk. I hated having to devour something quickly when I wasn’t feeling hungry, while my sister was the master of surreptitiously hiding food in the car door, and disposing of it when she got to school. Later, I’d learn I was slightly lactose intolerant which explained why I had the shits every time I got to school in the morning.

After a particularly bad round of grumbling, Mum had the bright idea:

“You guys love Maccas. Why don’t we just try and make our own?” My sister and I just couldn’t believe that Mum would try and make something so...foreign. So not Chinese! Dad thought it would be easier, cheaper, and I mean...surely we could make it better, right?

Oh how wrong we were.

For our first week of experiments, we went to the supermarket and bought ingredients. An English muffin, some normal beef patties (“Who knows what they put in sausages! Let’s get the healthier version”), egg and some plastic squares of Kraft cheese. When putting it together, Mum tried to keep the egg in a disc shape, but instead ended up scrambling them instead. The cheese didn’t melt, and we thought just eating the English muffin straight, like a bun, would be fine.

Not all experiments are successful the first time. We soldiered through some pretty terrible muffins, but there’s always room to learn, right?

The next week we tried it, Dad took over - toasted the muffins, got a new type of cheese (one of those actual cheese slices - Bega, or Coon. I forget), and still scrambled the eggs. It was closer, but the kids were still complaining. Ungrateful bastards.

Our gamechanger was when Dad found a little disc-shaped mould to crack the egg into, that would help keep it together. Progress was made - it even looked the part! But taste-wise, we were repeatedly disappointed, and we were never able to conquer the lofty heights of the McMuffin. There was just some extra, elusive element the Maccas muffins had that we couldn’t work out.

Can you believe the effort?! I didn’t realise it at the time, but my parents would wake up early just to try and recreate this dish, every day for nearly a month, to make us happy. Giving us some milk and making us cereal wasn’t good enough - they wanted to make sure their kids got the best they could give. They weren’t always effusive with praise or encouragement, but as parents, that was the way they knew how to show their love. And hey, this wasn’t the only dish they tried recreating! It was like we had our own Claire from the Bon Appetit Test Kitchen trying to recreate fun snacks and treats for us kids.

Their sacrifice only became clear to me recently. They had to wake up extremely early because they had full-time jobs, and we were both sent to private schools. That meant they had to drop us off, before getting to work on time, and then coming back out to pick us up on the way home. Our job was to be educated, their job was to make sure we could focus on being educated. On weekdays, it was their responsibility to make sure we were cajoled and bribed into eating breakfast, so that we’d have energy for the day. Saturdays were a way to indulge their comfort foods - yum cha and cha chaan tengs - memories of a youth passed in a country far far away. Sunday mornings were times they could relax, and give the kids a special meal for the week. A ritual of delicious, cheap, easy food.

For my parents, food was love. The sacrifices they made weren’t sacrifices to them - a parent’s duty is to make food, brew medicinal Chinese soups, and make McMuffins so that the kids eat breakfast. They pushed themselves to cook in unfamiliar cuisines so that we might have a better life, they weathered our complaining and griping for years, and pushed us to be our best selves.

Love isn’t just words. You can say just as much with your time and your efforts, your service and your strength, your selflessness and your sacrifice. They’ll know, some day.

In the end, we kept going back to Maccas.

An English muffin, a sausage patty, and a disc-shaped egg.

What’s so hard about that?

Hi Mum and Dad, Meet My Boyfriend

By Sabrina A.

5 minute read

From a young heterosexual, cis woman heralding from a conservative, religious Chinese-Indonesian family.

As a woman, I've had it instilled in me that one of the most important decisions I will ever make is the man I will have as my life-partner. Note, man. It was assumed that I could only ever be heterosexual, and nothing else. This man had to be carefully vetted for approval to ensure he met the unspoken criterion my family had for a suitable partner.

From my observations and interactions, the minimum expected:

Religious, in the right one - lest he lead me astray.

Has skin colour similar to own - the 'other' was unwelcome.

Self-sufficient, future household breadwinner - a man is always the head of the household and must have the capacity to solely sustain his family.

Not ugly - meeting a baseline minimum of objectively attractive aesthetics.

Demonstrates filial piety - will agree to taking care of elderly parents later on in life.

Kind - as an afterthought, and the last question to ask about him after the man has fulfilled the above.

Prior to the first meeting with my family, I have had to extensively prepare my partner to ensure maximum success. Pruning, preening, moulding his (and my) stories to appeal to my parents and gain their approval. It felt like we presented him as a different person to the one I know and love.

The first meeting was awkward. My family asked and said little, they were not accustomed to initiating small-talk. My partner tried to impress. He enquired about work, family, hobbies, the dog, anything to keep the conversation alive. We went through our rehearsed story of how we met and how long we had been seeing each other. While it was only an hour-long lunch, both of us were certainly glad to be done by the end.

It's funny how parents don't have much to say to your partner, but they will have plenty to say afterwards, casting judgement on the strangest of things, or nuances you didn't even consider at the time. I was told it was good that he was ambitious in his career planning, however it did not bode well for his family-tending behaviours in the future. His family heritage raised some question marks - how did he not know the specific nuances of what his father did? How was it possible that he had his licence and could not afford a car? Nonetheless, the overall assessment for now was: 👌. Phew, he had passed. For now.

How good are East Asians at showing love?

By Clinton Chan

10 minute read

How good are East Asians at showing love?

It’s not easy to know how you should love someone - we’re never taught how to love, who to love, and how your love should change over time. It’s also not easy to know “what good love looks like”. There isn’t a “gold standard” - though I’m pretty sure I’m not it (cries in singledom).

When I talk about “love”, I don’t mean just romantic love. I also mean familial love, friendly love, and even collegial love (your boss needs love too). Of course, figuring it out is part of the joy of love, nobody expects you to know how it works.

In the Western world, much that we know of love is still built on Shakespearean ideals.

But if you’re someone from an East Asian background and born into a Western society (like me), our concept of love is conflicted. As a straight East Asian man, for example, I’ve been taught a strictly Confucian idea of love that is stoic and based on filial piety. Yet in the films I consume, the novels I read, and even on dating apps, some aspects of Western society still promote either a chaotic Shakespearean “head over heels” affection or a low-key “10 Things I Hate About You” type love. This can leave some of us culturally conflicted in how we think about “love” and left without a measure for what “good” love looks like.

To clear the waters, I recently delved into the work of Dr Arthur Aron, a UC Berkeley psychologist who’s famous for his 36 questions to make you “fall in love” with anybody. His research on love isn't just about “romantic” love though, but also love as affection and admiration between people. In particular, Dr Aron’s four universal traits of healthy relationships struck a chord with me and got me thinking - if this is what “good” looks like in a biological and psychological sense, how does East Asian love compare?

Dr Arthur Aron of UC Berkeley is famous for his research on love, including the 36 Q questions to make people “fall in love”.

I want to dive into that, speak to my own experiences in love, and talk about how our cultural upbringing may hinder and empower certain expressions of love.

What is Love?

Baby don’t hurt me?

Dr Aron’s research focuses on how we build and maintain love over time based on four traits he studied in couples who felt they were very much in love. These four traits are:

Showing appreciation and gratitude;

Celebrating each other’s successes;

Doing things with your loved one that are new or challenging; and

Having friendships with other couples (I won’t discuss this one).

So how does love in East Asian communities compare?

Showing appreciation and gratitude

In Dr. Aron’s research, showing appreciation and gratitude to someone is key to extending love. It’s not just about thanking them for ways they’ve helped make you feel more positive or that time they shouted you a meal because it was the end of your pay cycle. It’s also about celebrating their overall presence in your life.

Showing gratitude isn’t something that comes naturally amongst East Asians.

If this is the “gold standard”, how do East Asians compare? I’m not going to beat around the bush – I don’t think showing appreciation and gratitude is the strong suit for most East Asians. If you’re one of the youngest in the family, you’re basically the lowest rung on the totem pole and expected to bend over backwards to show strong appreciation to elders, even if there’s no hope of reciprocation. This is particularly the case between parents and their children. Whilst your parents might expect a lifetime of kowtowing if they make you dinner or pay for your piano lessons, don’t expect a joyous “well done” if you passed your 6th grade violin exams.

Most of us have also probably noticed the lack of appreciation between parents or grandparents (or extended family members). East Asians often uphold the family unit as sacred, but I’ve seen plenty of couples or families that should have seen Dr. Phil agggess ago (or the culturally appropriate equivalent) based on the sheer lack of gratitude. It’s also uncommon for our parents or grandparents to be openly affectionate to each other to the point where you begin to wonder “how they even got freaky back in the day?”.

Whilst there are certainly exceptions, such as friend-friend appreciation and grandparent-grandchild appreciation, I do think that if we were to hold ourselves up to Dr Aron’s definition of strong “love” as showing appreciation, our love for each other may not be as strong as we'd like to admit.

Celebrating the other person’s success

Another crucial part of showing love according to Dr. Aron is not just helping a person at their weakest, but taking the time to REALLY celebrate their successes too, to make their achievements feel validated.

Celebrating successes isn’t just about showing appreciation and validation, but also finding ways to celebrate the little wins too.

As East Asians however, we sometimes have a curious way of celebrating each other’s successes. You probably remember hearing about it as a kid. The ol’ Saturday boast-off, where your mum and other mums have a casual catchup outside the supermarket or tutoring centre and it turns into a weird flex to see whose child is more accomplished.

But you only hear about it because your mother comes home and tells you how your family friend’s 8 year-old son is playing 7th grade piano, whilst acing his state Mathletics competition, and oh yeah Bill Gates wants to call him next week for a job interview… so why you so stupid and lazzyyy la??? And then your award for gaining a pen license last week fades into the ether…

Often as Asian children, our successes were boasted about rather than celebrated with us.

Whilst most successes are no doubt recognised, they aren’t nearly given the upbeat reaction that Dr. Aron describes in his research. I remember when I got into law school, there wasn’t so much as a pat on the back to congratulate me let alone a celebratory meal. No doubt I can’t speak for all East Asian families, but the lack of encouragement and congratulatory joy is definitely something many families lack.

This likely isn’t even the case between couples of family members. As East Asians we don’t really do “promotion parties” or baby showers. In some ways your successes are you meeting the bare minimum so a nod of approval and continued acknowledgment, as opposed to alienation, is often all you’ll get from family.

Doing things with your loved one that are new or challenging

While I’ve had a good rant so far, I do think most East Asian families and communities get this one right. To keep things interesting and to generate cherished memories, Dr. Aron suggests people should aim to constantly try new experiences with those they want to stay close to. Challenging experiences in particular can help broaden your own horizons and help you uncover facets of the other person you may come to like.

Obviously this is dependent on each person or family’s income, but I’ve noticed that East Asian couples, friends, and extended family alike do a pretty good job of keeping life interesting, whether it’s trying new restaurants, going for a holiday, or planning day trips to the seaside. What’s more, as we get older we generally grow our disposable income - so even if your childhood relationships with friends or family weren’t that enthralling, there’s no reason that the future doesn’t hold something brighter (how wholesome).

Trying new or challenging activities or ways of doing things is a tried and true way to build affection between people.

Are we any good at love?

If Dr Aron’s research is anything to go by, East Asians could do a much better job of things like showing appreciation or celebrating success. We really need to get around popping the bubbly rice wine (is that a thing?) or even family PDA.

On a serious note, I do think that the way we show love can be really subtle, and for second-generation migrants like me, a bit under the radar. The downside of this is that it can lead to resentment and emotional distance in intimate or familial relationships.

Hopefully, by reading this, you’ll feel inspired to be a better “lover” because it can only bring you closer to the people you care about.

Why are Asian Australians underrepresented in federal politics?

By Clinton Chan

10 minute read

Note: This blog is a heavy topic, so strap yourselves in

Why are Asian Australians underrepresented in federal politics?

“The Australia that I live in and the one that I work in, Parliament, are two completely different worlds”.

Those are the words of Mehreen Faruqi, a Greens senator and the first female member of Parliament. What Mahreen was eluding to was the sheer lack of ethnic diversity in Parliament when compared to the diversity seen in the towns and cities of Australia.

With the federal election coming up I’d like to dive into a topic that has weighed on my mind for decades: the lack of Asian-Australian diversity in federal government.

Since the Whitlam government’s full dismantling of the White Australia Policy in the early 1970s and embracing of multiculturalism, Australia has grown increasingly diverse, especially when it comes to welcoming migrants and refugees from Asia. As of the last Census in 2016 Asian-Australians (including South, Southeast, and East Asians) makeup approximately 16% of the Australian population.

Over the years Asian-Australians have grown as a proportion of the population.

But guess how many candidates of Asian heritage were elected in the last federal election in 2019? Just 5. A cursory look at the candidates from that election will also note a severe lack of Asian-Australians even picked to run in the race. The 5 that were elected make up about 2% of the 227 seats available - that’s a gap of 14%. Though it’s no doubt hard to get perfect proportional representation, we should expect to be edging closer to 36 Asian elected officials.

What’s more, this is a uniquely Australian problem. Countries like Canada, New Zealand, the US, and the UK are far ahead in terms of their parliamentary diversity, especially when it comes to the proportion of elected officials and candidates of Asian heritage relative to the population.

So what the frack is going on? Why is the representation SO bad, and why aren’t Asian-Australians given a chance to even make it to the starting line, let alone run the race?

In this blog I dive into some of the reasons for poor representation…

…

It’s racism, racism is the reason!!!

My blood is boiling as I did the research for this blog, and it is very easy to point the finger at racism or some level of discrimination. But at the same time, it’s REALLY hard to shore up the evidence to show that racism is the problem here.

I do believe though that some level of discrimination is systematic and that part of the problem is how multiculturalism is practised in Australia. Dr Devaki Monani, a researcher in multiculturalism puts it aptly when she says that many Australians from non-White backgrounds are “recognised first by their ethnicity” as opposed to their identities as Australians. As a result they are not considered truly representative candidates because for the major political parties, their voting base is still largely white (which is so wrong). On the other hand, those with European or Anglo-Celtic heritage, Dr Monani argues, are much more quickly absorbed into the political landscape and the Anglocentric idea of Australian identity.

Whilst Night Noodle Markets in major cities are fun, they are a surface-level way to engage with the lives and identities of Asian-Australians.

The former Race Discrimination Commissioner Tim Soutphommasane has also mentioned that multiculturalism in Australia is basically performative and “celebratory” - our approach to multiculturalism lacks “real engagement” and is largely based on funky foods and cultural festivals. This potentially leads to the perception that ethnic minorities are an oddity as opposed to Australian sub-communities with real voices and aspirations.

I couldn’t agree more with both - the fractious and sometimes disingenuous approach we take to multiculturalism and framing migrants (not just Asian migrants) as “ethnic” and not “true blue” is finally rearing its ugly head in federal politics.

At the same time, however, I recognise that there are other factors at play, some of which are outside of anybody’s control. Read on…

…

Party politics

For any member of a major political party, the path to candidacy can be fraught. There’s the jockeying, the competition to outdo other candidates, and the need to both learn and master the unspoken rules and party procedures to gain support for candidacy. All of this is naturally not easy for a new migrant in an alien culture and society.

What’s more, the seat you are running for and how “safe” it is at the next election has a massive impact. Even if you had the social capital from being a prominent member of your particular community or electorate, the party machine may still select somebody else because of the political clout and pedigree they bring.

Party politics is part of the reason why we aren’t seeing enough Asian candidates

This was clear to see when Labor veteran and former NSW Premier Kristina Kennealy was recently parachuted into the electorate of Fowler (the seat for Cabramatta, a suburb with a strong Vietnamese presence) for its pre-selection for the federal election, pushing aside local lawyer Tu Le who is of Vietnamese descent. The public outcry has been huge, and whilst Ms Kenneally has significantly greater political credentials than Ms Le, it’s obvious that difficult races are given to the most experienced runners, whilst diverse candidates stop being serious contenders. Alternatively, Asian candidates are also given “unwinnable” seats to run in, seats firmly held by the opposing party where their candidacy makes no difference to the political strategy of the party.

Not only are non-white candidates in Australian politics low on the totem pole, they are also included tokenistically. Asian candidates in particular are assumed to be the de facto representatives for their communities, and are often tasked with menial jobs like recruiting only party members and voters from the same background as opposed to working in a more advisory capacity to ministers or senior party leaders to learn the ropes. They are also often “punished” for not having wide appeal, and as a result, are just used as diversity fillers. It’s clear then that the major political parties in Australia are not taking Asian candidates seriously enough - they’re just cannon fodder.

The major parties’ unwilllingness to give political opportunities to Asian-Australians has also seen potential candidates stand for smaller political parties instead.

It’s not all grim though if the path taken by Gladys Liu, the federal member for Chisholm is anything to go by. Gladys, originally from Hong Kong, migrated to Australian in the 1980s and joined the Liberal party in 2003. She then spent 16 years competing for “unwinnable” spots and cutting her teeth in Victorian State Elections before she was given the federal candidacy in 2019. I don’t know how long it takes to get to candidacy in federal politics but at least she made it, and in a multicultural seat of Melbourne too!

…

Who represents us?

There is also the more nuanced problem of selecting representative candidates for ethnically diverse seats - there often isn’t a clear ethnic majority at all, making it hard to say that one seat is predominantly “Chinese” and should therefore have a Chinese candidate.

Let’s take the federal seat of Fowler for example, which houses part of the Sydney suburb of Cabramatta and has a significant portion of Vietnamese-Australians. You’d assume picking a Vietnamese-background candidate would make sense right? Not necessarily.

If we look at 2016 census data, those with Vietnamese ancestry makeup about 16% (the largest) followed closely by Chinese, Australian, and Italian ethnic groups. With no clear ethnic or cultural majority it can be hard to choose a candidate to “represent” the community if we are largely looking to find a representative on the basis of ethnocultural heritage.

It is partially for this reason that major parties have shied away from picking “diversity” candidates. As some commentators and former MPs like Ross Cameron have noted, at times parties can find it hard to choose one candidate amongst a pool of diverse candidates, and choosing a White candidate is “safer” because it “avoids triggering prejudices among different ethnic groups”. However, this also assumes that ethnic minority candidates can only represent their own specific community as opposed to minority communities at large, which likely isn’t always the case, though ethnic tensions (if present) are definitely a barrier.

…

It takes time…

It is important to note however that political engagement from ethnic minority communities often takes decades and perhaps even generations before these communities feel comfortable engaging in political life.

Researcher Grant Wyeth finds that this is particularly the case for refugees and other migrants who are economically disadvantaged and may need time to learn the language, build up their personal wealth, engage with the community, and build a career before thinking of entering politics.

As a result, it may take 1-2 generations before candidates from a particular ethnic community become politically active. We see this in the lives of politicians such as Tien Kieu and Meng Heang Tak who were born in Vietnam and Cambodia respectively, arrived in Australia in the late 1970s and 80s, and spent decades studying and working in Australia before entering state parliament in Victoria.

Tien Kieu left Vietnam at the age of 18 on a boat. 43 year later he’s a physicist who’s taught at Oxford University and MIT, and is now a Victorian state member of parliament.

Of the Asian-Australian ethnic groups that arrived in the latter half of the 20th Century, many are arguably well into their second and third generations in Australia and change is slowly creeping in. But the change is arguably too slow, particularly for Asian communities that make up such a large proportion of the voting public.

…

The future is (kinda) bright

Interestingly, the representation of Asian-Australians at the state level seems to be significantly better, at least for NSW and Victoria. Victoria and NSW see 10% and 9% of their MPs emerging from non-European ancestry compared to the measly 2% we see at the federal level.

Up until recently, we also had some solid partly leadership from non-European politicians too (though not necessarily Asian) with Elizabeth Lee leading the Liberals in the ACT and NSW’s favourite “iron lady” Gladys Berejiklian at the helm.

In the 2022 election, the sensitivity to the changing demography of key federal seats is also increasing. This is especially the case for the Chinese-Australian and Indian-Australian communities. Even though these groups are both incredibly politically diverse, the sheer number of people in these groups also means that more members of these communities will take an active role in politics and it will be hard to deny these groups a candidacy in key seats in future elections. In the 2019 election, both Labour and Liberal parties decided to run Chinese-Australian candidates for the seat of Chisholm (which houses the Chinese-majority suburb of Box Hill), with Gladys Liu winning and holding the seat today.

The light at the end of the tunnel is dim but tides are changing, and with greater solidarity amongst Asian-Australians I have hope that we can play an increasingly more decisive role and a louder voice in federal politics in years to come.

Want to read more about diversity in politics? I found these articles to be super insightful:

Mum, you were right

By Vincent Leung

6 minute read

Ever get into an argument with your parents about Chinese medicine?

My first memory of Chinese medicine was the overwhelmingly pungent smell of dried fungi and herbs in the cramped, musty shop off the main road in Box Hill. Walking into the office, the tinkly little bell sadly announced our arrival to a middle-aged, jovial-looking man. On our left was the faded, dirty glass that served as the countertop, set up in front of the wall-to-wall shelves packed in the traditional style.

I think the set up is mostly to scare you. Firstly, the shelves: know what any of these ingredients do? No? Well I do, so you better listen up - your life depends on it. Secondly, the dirtiness: sending the message that 'we're so busy helping you that we don't have time to clean'.

That makes sense, right?

The consultation always started with a three-finger pulse check on the smallest, flimsiest pillow in the world, and is usually followed up by looking at your tongue, looking at your general demeanour, asking about any particular injuries you've had, and then somehow telling you things about your body you never knew.

Mum would get the new soup recipe for the next few weeks, and then this particular Chinese doctor would prepare a set of small, black, spherical pills to take - 10(!) a day - that would help slowly improve your body's health.

The gnashing of teeth and wails of a young Asian kid who was bad at swallowing pills and hated drinking soups must be some of my mother's favourite memories. Imagine toiling away to find the exact list of 20 different ingredients that you can only get from the dingy back-sections of Chinese stores or apothecaries, boiling up some soup with the chicken bones you got for cheap at the butcher, and your kid is ungrateful for all this effort?! Parenting sounds like fun, hey?

I remember specifically that my qualm with Chinese medicine was how unexplainable it was. Western medicine is extremely good at proving that it works through a scientific method - randomised control trials over multiple clinical trials - and explaining how your body is going to respond to the medicine (including side effects and recommended treatment stages). The medicine will usually have a well defined action mechanism. It'll work quickly, and it'll work pretty much exactly how they say it will. On a cellular level, they can explain exactly what they're trying to target and what your experience is going to be.

Chinese medicine takes four months, it might or might not work, and the only explanation is 'yeah, it's going to make your liver feel better'. If you go back for your monthly check-up, and it hasn't worked well, then 'oh well, you'll just have to keep drinking it 'til it works'.

What?!

All I hear in my head is my Mum's exasperated tone telling me that it's useful, it works, and that 'there's no harm taking this at the same time!' and, 'look, it worked after these four months while you were also taking your Western medicine as well'. I feel like I have Stockholm Syndrome from drinking all these damn soups, but I think I've argued every single little thing that I can about why Chinese medicine makes absolutely no sense at all and why it should be struck from the Earth. You're wrong, Mum!

And yet...

I had a medical emergency last year, and the doctors couldn't work out what it was. It was too fleeting and sporadic to understand, the blood tests didn't really show anything, and there was no real course of treatment that they could recommend. I also survived, which meant it wasn't deadly, but still, it was a scary time. In my moment of weakness, I agreed to try Chinese medicine.

We did a combination of Western and Chinese medicine, and this time round...well, I thought more about whether I wanted that Chinese medicine or not (mainly because I was paying - that dried stuff ain't cheap!).

This time, I tried asking the doctor a lot more about why and how they were deciding what to give me. No black pills this time (it was packets of pre-packed ingredients to be boiled in soup twice daily), but definitely a lot more thought into understanding why certain soups were being boiled, why ingredients were being changed and adapted every month, and what was going to happen to my body.

And honestly, I still didn't understand it all.

However, as I slowly improved over time, I thought a lot about it. Why had I been so against it for so much of my life? This is the medicinal culture of my heritage, and I was deciding it wouldn't work because it couldn't be empirically proved through the Western medicinal lens. Why did that matter so much? The evidence in front of my eyes is that it works. Maybe not exactly the same as Western medicine, and maybe not as quickly, but it still works, right? Why? How?!

What I landed on was that the key reason that Chinese medicine has persisted so long is because it's been the longest trial and error experiment ever. This complicated set of metaphors and conceptualisations of qi (氣) and bodily yin-yang (陰陽) have persisted across millennia. Chinese people have used the combination of their observations over years to build a framework of ingredients and medicines that will heal people, and solve health problems using the natural ingredients at hand.

I'm not a doctor, and this isn't medical advice. I understand that Western medicine is much better at dealing with the symptoms of health problems, and I'd much prefer to go to an emergency department at a hospital rather than a Chinese doctor in the middle of a medical emergency.

But for long term health, Chinese medicine is still a valid choice in my mind. I might not have to go see a doctor, but I'm growing more of an appreciation of soups and the herbal, medicinal properties they provide.

I look back on the arguments I've had with my Mum and realise that maybe there was something to what she was talking about. Not all the way, but some of it - both of us fighting for what we think is true in a clash between Chinese tradition and Western science, and both coming away with a better understanding on the other side.

Unfortunately, as much as I hate to say it - Mum, you were right.

Three Thirsty Monks

By Vincent Leung

4 minute read

There was a wonderful play written by Anchuli Felicia King called 'Golden Shield' that told the fascinating story of the struggles of a courtroom battle, suing a company that had helped to build the Great Firewall for China, leading to the arrest and detainment of many activists in China.

In it, there was a lovely, fourth-wall breaking character called 'The Translator', who not only translates Chinese to English at different points in the play for the audience, but also explained the differences in meaning for the different idioms in English and Chinese.

In the opening monologue, he compares two sayings;

“三個和尚沒水喝” (‘Three Thirsty Monks’) with “Too many cooks spoil the broth.”

Want to learn something new? Let's try to understand what that first saying means.

…

三個和尚沒水喝 -

‘The Three Thirsty Monks’

Literal translation:

三個 - Three

和尚 - Monks

沒水喝 - Without water to drink

There was once an abandoned temple at the top of a mountain - it was dirty, dilapidated, and the well was dry. A passing monk happened upon this temple, and stayed to try and help repair it.

On his own, he had to go down the mountain, bring up water to drink in two big buckets from the river, and to help fill the well for his own uses. He spent his days praying, cleaning, and bringing water up the mountain. Absolute serenity.

One day, another monk came up the mountain in a daze, looking for something to eat, and something to drink. The first monk gladly shared what he had. When they ran out of water, they both went down to get it, sharing the load between them.

A few days later, yet another monk came up the mountain looking for water (was there a water shortage? how come so many monks were thirsty??), and when he got to the temple, thirstily drank the rest of the water from the well. He also decided to stay as he recovered from his (assumed) dehydration.

However, from then on, the three monks did not get any more water for the well - nobody wanted to let the other person just get it for free, and the responsibility fell by the wayside. They would instead go and get water for themselves as required, and no-one filled up the well.

Soon afterwards, by some divine narrative providence, the temple caught fire! The monks tried to get the water from the well to help put it out but alas, - there was no water. They had to run down the mountain in the dark many times to bring water up from the river to put the fire out the entire night, slowly putting it out little by little.

Assumedly, through this bonding experience, the monks learned to live in harmony and probably instituted a rotating roster of water-fetching to the chores list.

…

As the Translator notes in his monologue, the closest proverb in English is something like ‘Too many cooks spoil the broth’…but it has a bit of a different take.

In English, the saying tries to get across the fact that if there is too much input into something, these inputs will all clash, and 'spoil the broth' with too many different ideas.

In Chinese, the saying states that there are three people responsible, but no-one ’is actually accountable for what needs to be done - essentially, if it’s not clear who needs to do what, no-one will do anything.

There's not really a saying in English that directly maps to the Chinese, and vice versa. So how do we translate the idea?

…

Language is really powerful. It shapes cultures, ideas and memes for a population. For the diasporic Asian identity, we straddle the boundaries between two worlds often, and partake in the buffet of languages on both sides of the fence. We understand better than most the power of translation - the struggle of trying to help your parents understand an alien world, conforming to the stories heard from them, and at the same time adapting yourself to your surroundings.

…It's hard…

This difficulty of translation and language is something that plays out in more than just language across the world. We lack the understanding of other people’s contexts and how their culture has been shaped - the stories don't easily translate. Without any empathy or knowledge about what other cultures are trying to do, or achieve, or what experiences they've collectively gone through, how can we understand them?

This is already a long piece, so let's just end with: read some more about whatever Asian culture you're part of, or interested in. Take the time to ask about those sayings, those stories, those tidbits of culture that bring more context to your understanding of those worlds. Spend time being curious, and uncover more ways of looking at the world.

And look out for thirsty monks.

Advice from our Ancestors

By Vincent Leung

6 minute read

Rules of being an Asian child:

Listen to your parents, no matter what.

Take your shoes off at the door.

Never date until university and then as soon as you graduate, get married and give your parents a requisite amount of children for them to dote over.

The rest of the rules are really just about drinking warm water, wearing warm clothes so that you don't have to turn on the heating, and then drinking warm herbal soups for medicinal purposes. Very temperature-based rules.

…OH! and haggling for literally everything you can.

…

My grandparents had a lot of these sorts of rules that they lived their lives by - an accumulation of a lifetime of practiced experience. Things had to go in the right places. Fix things, rather than buy things. Keep using things until they are ragged, sweating the small stuff so you can save for the big stuff (which you would wait until there was a discount for anyway...and then it was a 50/50 whether you'd actually buy it).

I didn't have the traditional 'wow my grandparents are spoiling me' type experience - I had the 'practicing violin for an hour every day is for your own good and I'm TIMING YOU' type experience. My grandma had iron-clad rules that served her through a war, a harrowing migration, navigating a strange new (white) world, and successfully looking after herself way into her 90s. Her discipline had worked for years, and that’s how she would care for us. That discipline was love.

There’s space for a sixth love language, right?

When I got to university, my 婆婆 ('Po po' - i.e. grandma) gave me a lot of advice:

‘Make sure you go to class and attend everything you can. - don't go out too much because you need to study hard.’

‘You need to know people to do well in law! It's all about relationships. - make sure you're making friends, but STUDY REALLY HARD. - you can't fail either otherwise no-one will hire you.’

‘Don't date - you'll lose focus on your studies!’

Can you see the trend?

I always thought the advice was so outdated. Sure, I'll study for exams, but looking around, it wasn't the only thing people were doing at uni. They were joining clubs, skipping lectures, and still passing their exams. Reading and writing wasn't the only way to go about things anymore, and dude - I needed to find a girlfriend!

I watched as more ‘traditional’ Australians lived life in the world and enjoyed their lives, instead of being packed away in hushed libraries and grim tutorials. The only sliver of joy I had was feeling superior to everyone who hadn’t studied all semester cramming at the end of it.

Still, I discarded most of my grandma’s advice. I mean, I still studied (I'm not an animal) but I discounted the rest of it because I didn't think she really knew what she was talking about.

I considered it...the stuff you say. Rituals. Like when I learned how to say 新年快樂 (Happy New Year), 身体健康 (Stay Healthy), and 龍馬精神 (Have the energy of a dragon and horse COMBINED) at Lunar New Year to get the red packets - it wasn’t the meaning I was learning, just the words to unlock the reward. I thought the advice from her was just regurgitated from a book or something, rather than passing on her actual experience, and I would provide the expected 'yes 婆婆 of course I'll do that'.

It was only in the last weeks and months of my grandma's life that I sat down to dive deeper into her life. We had heard a lot of snippets about how she survived the Second World War and the Japanese occupation, but I got a lot more stories that were, well, understandably racist. She was one of the first Asian women who worked in government in Hong Kong, and she uprooted her whole life to migrate to Australia to follow her kids. She was a wonderful woman who went out and got what she wanted - a woman of action that I wish I had got to know a lot better.

But she never went to university. She was lucky to be able to study at high school, but further study wasn’t an option. She spent a lot of her life as a secretary, but used her razor-sharp mind to constantly analyse the world around her. She refined her English in a strange new land, she mastered a little corner of the stock market for her own little nest egg, and in one of my favourite stories, she made her own slingshot to scare off a black goose that kept coming into her backyard. She didn't take any shit, and held as many grudges as she could because she hated being taken advantage of.

The advice she had given might not have been specifically built off her own experience, but she had the smarts and courage to just…work it out. The practicality of taking charge of your life and sorting it out was what I was missing as a heady teenager thinking I knew it all and that ‘she’d never understand’. Uprooting your life and striving to make a better one in a new country builds character, and though the risk is harsh, the reward is worth it.

I'm sure your parents and grandparents have similar stories of struggle. The sacrifices they made, and the opportunities they never had - they live through you. They're trying their best to help you get through things, and often, they'll reveal pearls of wisdom you never really thought about.

…

Grandma told me to care about relationships, and I think about the wide network of friends and colleagues I have now, and how instrumental they are in helping me travel through life.